- The faecal-oral route refers to the unintentional transfer of microbes from the gut or faeces of one animal (including humans) to the mouth of another.

- Food businesses must ensure that both personnel and visitors do not contaminate fresh produce. This is achieved through appropriate the provision of appropriate and sufficient hygiene facilities, hygiene procedures, codes of practice, and effective training.

- All personnel must be trained in their specific hygiene responsibilities related to fresh produce handling. It is advisable for businesses to validate handwashing procedures.

- Studies have demonstrated that the lowest levels of bacterial transfer are achieved when workers:

- wash and dry their hands

- wear gloves

- then sanitise their gloved hands

- To reduce contamination risk, hygiene facilities must be:

- maintained in sanitary condition

- sufficient in number for the workforce

- equipped with effective hand cleaning and sanitising provisions

Worker hygiene and facilities

In summary

Faecal-oral route contamination

Many of the pathogens responsible for foodborne illnesses linked to fresh produce are transmitted via the faecal-oral route (1). This refers to the unintentional transfer of microorganisms from the faeces or intestines of one individual, human or animal, to the mouth of another. Pathogen transfer can occur through direct contamination of produce or indirectly via soil, water, equipment, or hands that come into contact with the crop.

Identifying ill workers is not always possible. Some may hide symptoms, suppress them with medication, experience only mild illness, or be completely asymptomatic (2). This makes it difficult for employers to assess risk. Nonetheless, infected workers handling produce, or equipment can inadvertently spread pathogens to consumers. Pathogens present in a worker’s gastrointestinal tract can colonise another human and can be shed in faeces in high concentrations. Thus, even small contamination events may result in illness.

The greatest risk of contamination is from a worker’s hands shortly after defecation (3). Hands contaminated with Hepatitis A, for instance, have been shown to remain infectious for up to four hours (4).

It is therefore essential that:

- toilets are sanitary and do not contribute to contamination

- toilets are accessible, meaning they are located close enough to the working area

- adequate numbers of toilets are available for the workforce

- handwashing and sanitising stations are available and used properly

- toilet facilities reflect the cultural expectations of the workforce (e.g. squat latrines where appropriate)

Personal hygiene and the role of training

To minimise the risk of fresh produce contamination, businesses should ensure that personnel and visitors do not cause direct contamination. Informing staff and visitors about hygiene expectations through training, sign-in procedures, and clear signage helps reinforce appropriate behaviour. Procedures should be checked periodically to ensure they are being followed correctly.

Although hygiene expectations often seem like common sense, businesses may be uncertain about the level of detail required. Research is limited in this area but does confirm that human pathogens can persist on hands and produce surfaces after cleaning. Clear guidance is available from the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC), which operates under the FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme.

Three key CAC codes of practice relevant to hygiene in fresh produce are:

- General Principles of Food Hygiene (CAC/RCP 1-1969, Rev. 6-2022) (4) - applies to all food types

- Code of Hygienic Practice for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables (CAC/RCP 53-2017) (5) - specifically for fresh produce

- Guidelines on the Application of General Principles of Food Hygiene to the Control of Viruses in Food (CAC/CXG 79-2012) (6) – applies to all food types

CAC hygiene recommendations include:

- Excluding workers suspected or known to be ill with food-transmissible illnesses from food handling areas (no defined exclusion duration). Expecting workers to report illness to management (no specific system for implementation provided).

- Ensuring that workers directly handling produce maintain a high level of personal cleanliness:

- wash hands before handling produce, after toilet use, during breaks, and after contact with potential contaminants

- wear appropriate, protective clothing and waterproof dressings for cuts or wounds to create a barrier for bacteria from the wounds contacting the produce. Record and check the use of wound dressings in direct produce handling

- Behaviours that risk contaminating produce should be prohibited. These include:

- smoking, spitting, chewing gum, eating, sneezing, coughing

- wearing personal items (e.g. jewellery or watches) in production areas

Training

According to CAC5, all workers must understand the importance of hygiene and the role they play in producing food hygienically. Training should be tailored based on a worker’s level of risk involvement in potential contamination, pathogen growth, or post-harvest handling.

Training should include:

- personal health and hygiene

- handwashing techniques

- proper use of toilet facilities

- safe fresh produce handling

Regular refresher training is essential to ensure continued hygiene awareness. Further detail is available through the Red Tractor Fresh Produce Standard.

Handwashing and hygiene validation

The importance of effective handwashing in preventing cross-contamination cannot be overstated. Unwashed human hands are known to harbour a wide range of microorganisms, including pathogens that can cause foodborne illness.

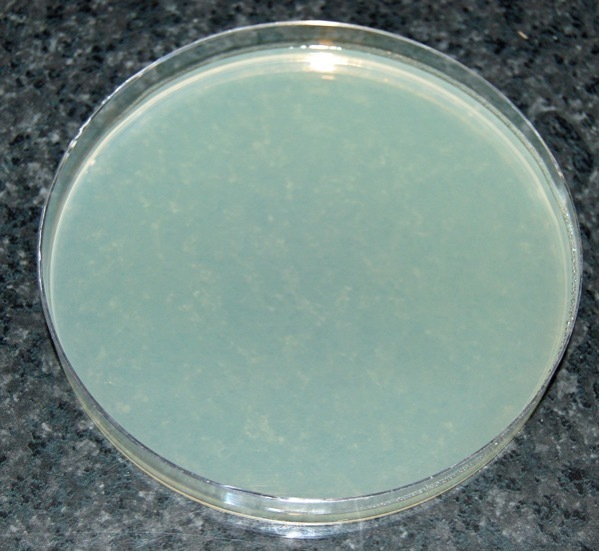

If a person presses their unwashed fingers onto a non-selective agar plate (that supports microbial growth) and the plate is incubated at 25°C for 48 hours, typically a high number of microbial colonies appear, as demonstrated in the image below:

Figure 1: Images of an agar plat with a human handprint after not washing, washing with water only, washing with liquid soap and water, and washing with liquid soap and water and additional use of an alcohol-based sanitiser.

Unwashed hand

Washed in water only

Washed with liquid soap and water

Washed with liquid soap and alcohol sanitiser

These results illustrate that unwashed human hands can be a significant source of contamination. Therefore, handwashing must be conducted frequently and correctly, especially by workers who handle food. Using only tap water to wash hands typically results in a minimal reduction of surface microorganisms. This demonstrates that water alone is not effective at removing microbial contamination and is unsuitable for use in food production areas. Washing with liquid soap and water significantly reduces microbial contamination. Soap acts as a detergent, removing oils from the skin where microorganisms reside. Additionally, it can damage the outer membranes of some bacteria, resulting in their death. In the image, the visible reduction in white bacterial colonies indicates the effectiveness of soap. However, some microorganisms (e.g. the reddish colonies) may remain largely unaffected by soap alone. Using an alcohol-based sanitiser after washing with soap and water can result in an even lower level of recoverable microorganisms.

This combination, thorough washing followed by alcohol sanitisation, provides an effective means of controlling contamination from workers’ hands during food handling (7).

Validation of handwashing procedures

Food businesses should validate the effectiveness of hand or glove washing procedures. This is particularly important when reusable gloves are used. In such cases workers must wash their hands thoroughly before donning gloves. Gloves themselves must also be washed and sanitised if reused. Effective use of gloves (either disposable or reusable) and handwashing procedures is part of initial employee training in many businesses.

A simple validation method consists of pressing the workers’ hands onto agar plates before and after handwashing and sanitation. Incubation of the plates to observe whether contamination has been sufficiently reduced. Repeating the process as needed until satisfactory results are achieved. Another, more involved, method is quantitative validation. Here, a diluent-soaked swab is used to sample microbial levels from hands, including hard-to-clean areas such as between fingers and under fingernails. Swabs are then plated to obtain bacterial counts. Statistical analysis can be used to determine whether reductions in microbial levels are significant.

More guidance on validating sanitation methods is available in dedicated resources for comparing reductions in microbial loads.

The use of gloves, alcohol gels, and the importance of drying hands

In a study investigating the effectiveness of gloves as barriers to bacterial transfer between hands and food (e.g. lettuce), bacteria were found to pass from food through gloves to hands and from hands through gloves to food (8). Wearing gloves reduced bacterial transfer to 0.01%, compared to 10% when no gloves were worn. Gloves are therefore not a perfect barrier. Proper hand hygiene before donning gloves is essential.

In a review of sanitising agents, it was found that alcohol gels are effective against most Gram-negative bacteria, which include the majority of pathogens associated with fresh produce (8) and against many viruses including Norovirus (9). Listeria monocytogenes, a Gram-positive pathogen, is an exception and may require different control methods.

Alcohol gels are only effective when hands are only lightly soiled. When hands are heavily soiled, antimicrobial soaps are equally or more effective than alcohol gels. Alcohol gels have no residual effect, whereas some antimicrobial soaps continue to offer protection after handwashing. Another study found that while handwashing with soap and water was effective at removing soil from workers’ hands, it was poor at reducing bacterial counts on hands. The study noted that there were benefits of using alcohol gels in places where water for handwashing was unavailable (10, 11).

Antiseptic wipes can be useful where water is unavailable, but they have limitations, they are not effective if hands are more than lightly soiled, they have only limited efficacy against enteric viruses and should not replace proper handwashing where facilities are available.

Residual moisture on hands after washing significantly increases microbial transfer. Proper drying is critical to limit the spread of bacteria via touch-contact surfaces (7).

Distance and provision guidelines for hygiene facilities

Accessibility of hygiene facilities is critical. The Codex Alimentarius Commission recommends that toilets be situated close to the fields or processing premises. The Global Good Agricultural Practices (GLOBALGAP) standard sets a maximum distance of 500 metres, and the United States Good Agricultural Practices (US GAP) standard specifies ¼ mile. Although Red Tractor previously adopted the 500 m guidance, it now simply advises that toilets be located far enough away from crops to avoid direct contamination.

The 500 m maximum is supported by data from a study, which found that longer distances between toilets and fields correlated with higher levels of Escherichia coli, coliforms, and other pathogens on crops (3). In exceptional cases, such as for lone workers, facilities may be placed further than 500m, but only if adequate transport to the toilet is provided.

Toilets must also be cleaned and sanitised regularly. It was found that field toilet door latches and handles can contain up to 1,000 cfu/cm² of aerobic bacteria and significant numbers of viruses, underscoring the importance of regular disinfection (7, 13).

The UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) offers detailed guidance on toilet and hand basin provision for employers, as shown below (14).

Table 1: HSE recommendations for mixed-gender (or all-female) workforces

| Number of workers | Number of toilets | Number of hand basins |

|---|---|---|

| 1-5 | 1 | 1 |

| 6-25 | 2 | 2 |

| 26-50 | 3 | 3 |

For all-male workforces, the HSE provides an alternative recommendation:

Table 2: HSE recommendations for all-male workforces

| Number of workers | Number of toilets | Number of hand basins |

|---|---|---|

| 1-15 | 1 | 1 |

| 16-30 | 2 | 1 |

| 31-45 | 2 | 2 |

| 46-60 | 3 | 2 |

| 61-75 | 3 | 3 |

| 76-90 | 4 | 3 |

| 91-100 | 4 | 4 |

These recommendations do not constitute legal requirements under The Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992, but are considered best practice, especially when working with high-risk fresh produce. While many quality assurance schemes do not specify toilet numbers, Red Tractor advises at least one toilet per 20 workers, aligning closely with HSE guidance for all-male workforces.